Hargeysa Ideas II, 2014 – in Conversation with Nuruddin Farah

Ideas do not belong to anyone. They help society to grow up collectively as well as individually, and every member of the society needs them. Hargeysa Ideas is series of cultural study publications, based on analysis and views expressed by one of the Hargeysa International Book Fair guest artists in each year. Each issue is initially formalized as a live conversation, with the possibility to have question and answers session that involves the public; and in a subsequent moment the guest artist, with the editor, expands the conversation with possible additional questions.

This year the HIBF had as prominent guest Nuruddin Farah, one of the most important African writers and the author of 14 books, amongst them From a Crooked Rib; The Naked Needle; Yesterday and Tomorrow; Territories; the trilogy: Sweet and Sour Milk, Sardines and Close Sesame; the trilogy: Maps, Gifts and Secrets; the trilogy: Links, Knots and Crossbones, etc. Born in Somalia, he grew up in the Somali-speaking region of Ethiopia, studied in India and the UK, and has long been residing in exile. Now based in South Africa he teaches in the States and travels extensively during the year.

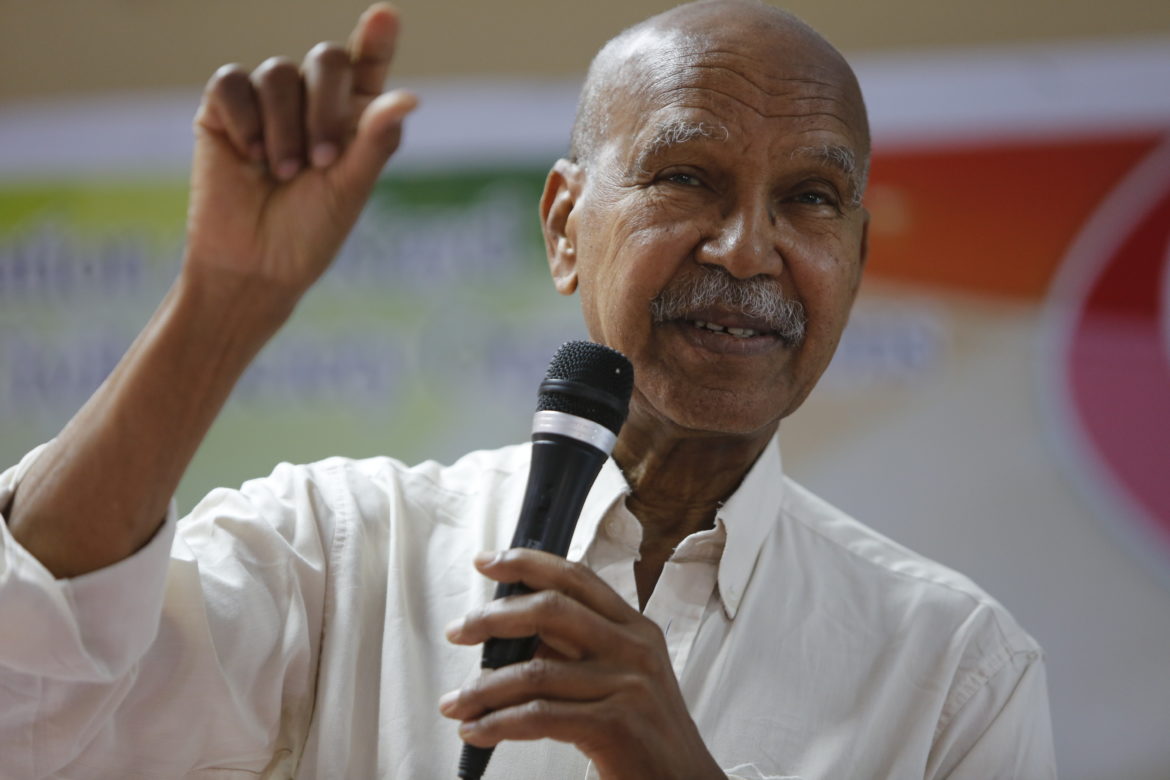

Jama Musse Jama: Nuruddin is here as a guest for the 7th Hargeysa International Book Fair. Thank you for taking the time to talk to me. Let us start with the Book Fair. This is the first time you join us for the fair. What did you expect to see in Hargeysa and what, after a week-long programme of events, have you observed?

Nuruddin Farah: I expected to find at the book fair a large number of books published from outside the country and was pleased to see that there have been attempts to publish texts written in Somali. Above all, I was highly impressed with the quality of the books published by your outfit Redsea.

JMJ: The imagination was the theme of this year’s festival, which allowed several different people to address the topic from a variety of perspectives. We also struggled initially to agree on how to translate the word ‘imagination’ into Somali : mala’awaal, khayaal from the Arabic, suurayn, etc. Would you like to say something about the theme?

NF: I was very delighted to listen to the ongoing debate between the speakers as to what Imagination meant to them, especially the poems authored by the young men and women who participated from the floor.

JMJ: This year Malawi featured as the Guest Country of the year. We hosted the outstanding Professor Mapanje and Dr. Msiska amongst others. Next year we will be inviting Nigeria as our Guest Country. We insist on hosting an African country as our guest also because we want to open ‘a window’ of communication between young Somalilanders and African cultures and literature. What do you think about promoting cultural ties across Africa as well as with Europe (through the diaspora) and the Gulf of Arabia (due to its geographical proximity)?

NF: I would prefer more close contact with Africa, less with Arabia. Personally I feel much closer intellectually and geographically with our continent and was delighted to see the participation of several of my Malawian friends at the Book Fair.

JMJ: Hargeysa International Book Fair is becoming a truly international event which takes place in a peaceful corner of a troubled region. You met with several friends such as Jon Lee Anderson, brilliant young writers like Nadifa Mahamed and many others, and they were keen to meet and converse with you in Hargeysa. What message about Somali culture do you expect these authors, journalists, thinkers and artists to convoy to their respective communities?

NF: I believe they arrived with little knowledge about the Somali-speaking world and they left with a better understanding of our culture and our worldview.

JMJ: Throughout your stay in Hargeysa for the Book Fair, you also had the opportunity to visit the decorated shelters of the Laas Geel caves. What impressed you about these cultural sites?

NF: I was moved to see the figurines and felt more convinced than before that we, Somalis, have our way of worship, our way of looking at the world long before Islam arrived in our land. And I hope that we will know more about the origins of these shelters and the reasons why they were created in a future to come.

JMJ: Culture shapes individuals’ worldviews and the ways in which communities address the changes and challenges faced by their societies. To what extent do you think culture has become a priority in Africa and in Somaliland?

NF: Culture tends to bring peoples closer and has also the tendency to create changes in the way we perceive ourselves. It was moving to note how much the Book Fair meant to the residents in this city.

JMJ: The connections between culture, art and development have been increasingly recognized at an international level. For example, UNESCO is deploying an agenda of mainstreaming culture into development, and aims to introduce culture as a priority in a post-2015 UN Development Agenda. Do you think there is an opportunity for culture to take center stage in Somaliland?

NF: It’s been my belief that only by giving more priority to creating written culture, recording our oral literature and by committing more of our efforts to promote the written tradition that we will achieve more developments both in our daily lives as well as in our national cultures. The debate has begun here at the Book Fair and I am pleased to have been a participant in it.

JMJ: A mainstream understanding is that ‘culture is a vector of socio-economic development,’ and a potential for boosting socio-economic growth and employment through cultural industries. Do you see any tangible contributions that can be gained through promoting culture and heritage in the Somaliland economy and the country’s development?

NF: A lot needs to be done for us to promote the healthier aspects of our culture and to exploit the potential that is there.

JMJ: A second interpretation of the relationship between culture and development is to consider culture as “capacity to inspire”, to develop a decent human being, and to produce sustainable wealth in a process which is “based on heritage, diversity, creativity and the transmission of knowledge” that relate culture to all dimensions of sustainable development. Are we distracted by the globalization in producing profit at all costs, from humanizing the development and focusing on the individual?

NF: Culture, when approached with a more progressive secularity serves as a well-rounded, less limited and less limiting way and not when we approach it from a narrow-minded, constrictive manner.

JMJ: Let’s return to discussing Nuruddin as a writer. You are now living almost permanently in Cape Town, in your apartment, which I imagine is in a silent and comfortable place which gives you time to think and write. What is Nuruddin’s standard daily routine in South Africa? When does Nuruddin Farah write for instance?

NF: If and when possible, I write daily from 9am to 5pm. Sadly, there are continuous interruptions, in that I travel a great deal, away from my comfort zone. But at least I would like to make sure that I spend about six months a year doing the writing in Cape Town

JMJ: I do not want to go back to the same question about why you do not write in Somali. But you are probably well aware that some people criticize the fact that your writings, and the characters and the places that you mention in your books have Somali names, but are not Somali in spirit and do not reflect the ways Somalis behave. They claim that your characters portray a Western style of life in a Somali context. What is your response to that?

NF: My response is that most of the Somalis who criticize me have seldom read any of my books, because those who do read them, are more kind to my efforts at writing.

JMJ: Is there a specific target audience, or readership in your writings?

NF: Every one of my novel has ‘found’ its own audience and I am pleased to say that there are some readers, foreigners and Somalis who admire them even more than I do.

JMJ: Your books have been translated into a dozen languages, with the exception of Somali. Would you like to see your novels read in Somali? Are there any plans to do so? Is anyone working on it?

NF: I would very much love to see several of my novels translated into Somali and I hope that Redsea/Kayd will make this happen.

JMJ: I heard a friend of mine who said that when Nuruddin’s writings first came out, people who did not know about him, confused whether the narrator ‘I’ of the story was in fact a women. Where did you gain this sensibility to women’s issues in your early writings?

NF: In truth, the story on which I based FROM A CROOKED RIB is the story of many Somali women and as a matter of fact I even met a woman who claimed that since the story was hers, perhaps I should consider sharing the royalty with her.

JMJ: You are identified as the first writer to break with the Somali oral tradition. Now, Somali literature is in a transition period, shifting from orality to the written word. What are we losing, and what are we are gaining?

NF: The way I see it: I am forever indebted to the Somali oral tradition, which I employ to prop up my writing, assist me in my self-identification with being a Somali. Much of my writing, as a matter of principle, is informed by my borrowing from the Somali oral tradition, despite acknowledging that, as things stand, the Somali oral literature will remain the poor cousin to the written tradition until we organize the recording and dissemination of it via the technological media that are available to us. Even so, with every gain, there is a loss that comes with it. However, in order not to lose much, we must commit ourselves to recording our oral traditions in order to make the transition work to our advantage.

JMJ: I know you do not sympathize with the oral culture and you chose a long time ago to move to the written. On the other hand, Somali oral literature, mainly poetry, is not only rich but also very sophisticated (for instance the scansion system). Are there elements of this oral tradition that need to be preserved at any costs?

NF: It is unfair to accuse me of “not sympathizing” with oral culture. Rather, I do wish to romanticize it.

JMJ: But I heard you labelling the oral literature as the poor cousin of the written literature. Why do you consider it as such?

NF: Because there is something terribly “primitive” about oral culture – and for it to reach more people or even to survive, it cannot do so without technology.

JMJ: Now, on another perspective: is there a specific form of literature that one can call African Literature?

NF: My feeling is that any text written with informed African sensibility belongs to African literature. Africa is a multilingual, multicultural continent and in my discussions I insist that North African literature, whether written in Arabic or French is as an integral part of the continent’s literature as the texts produced white South Africans or other African nationals from the continent’s South of the Sahara.

JMJ: Most of the contemporary African writers are in some way formed and shaped in and by the

West. Can we still call them African writers?

NF: We do and we can and we must. As long as they think of themselves as Africans and their writings as part of the continent’s literary production. I tend to take an inclusive stance and am not enamored of the exclusive tendencies shown by narrow-minded literary critics.

JMJ: Africa is not a country. There are 54 different states, 3000 different languages, … why is there an obsession to talk about Africa as a uniformed society? What do all these countries have in common?

NF: These countries share an African sensibility not found elsewhere. Of course, there are differences among the separate regions of the continent, just as there are differences, say, between Sicily and Sweden on the one hand and England and Italy on the other.

JMJ: In a session of HIBF2014 on “How to write about Africa” you blamed the African writers for not writing enough on Africa. Did you intend the quality of African writing not being developed enough in such a manner to influence the world and change the opinion on Africa, or it is (also) for matter of quantity? We write less than others….

NF: We in Africa produce less writing of exceptional quality than any other continent. That is for sure.

JMJ: You just finished your new book, which will be launched in two months of time. Can you tell us anything about it? At least the title?

NF: The new novel, which is the first part of a new trilogy, is called HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT.

JMJ: Are you working on a new project?

NF: I am currently at work on the second part of the new trilogy.

JMJ: Are you coming back for the next HIBF? We would love it!

NF: I hope to return when Redsea Culture Foundation publishes the translation, into Somali, of my first novel.